Michael R. Caudle, M.D. and Anna Taubenheim, PsyD, are part of the team at Cherokee Health Systems in Tennessee. Parinda Khatri, MD, CEO at Cherokee Health Systems serves on our National FQHC Advisory Board.

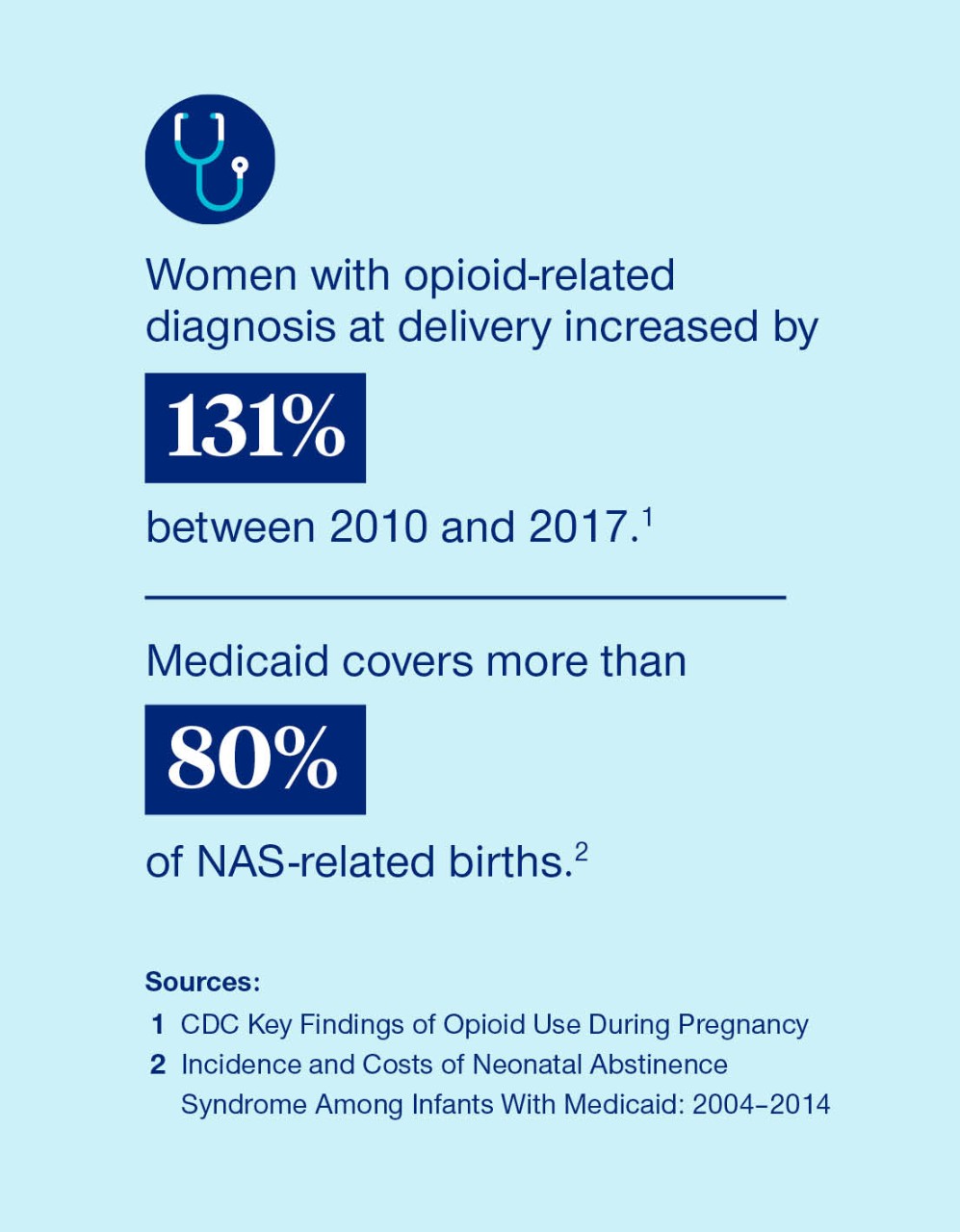

Opioid use disorder (OUD) has become a public health crisis for all populations including pregnant individuals. Women with opioid-related diagnosis at delivery increased by 131%, between 2010 and 2017.1

Pregnancy is a particularly critical time to address opioid use disorder, as prenatal opioid use is associated with maternal death as well as serious complications for the baby. Women may also be more receptive to seeking treatment during this transitional period of their lives.

Knowing that many prenatal programs fail to address the mental health conditions that either contribute to the development of addiction or occur with it, Cherokee Health Systems (CHS), a rural FQHC in Eastern Tennessee, began offering integrated care along with medication-assisted treatment to pregnant women with OUD. They hoped to improve outcomes for the mothers and babies and reduce the risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS).

NAS is a group of conditions that occur when a baby withdraws from certain drugs they are exposed to in the womb. Babies with NAS may be born with low birth weight and are at an increased risk of jaundice, seizures and sudden infant death syndrome. Infants born with NAS often need to be treated in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Medicaid covers more than 80% of NAS-related births.2 Infants with NAS have longer hospital stays than infants without NAS. According to the Tennessee Department of Health, NAS cases rose from 338 in 2014 to 366 in 2015.

Medication assisted treatment (MAT) is seen as a best practice for treating pregnant women and mothers for opioid use. MAT uses medications that prevent withdrawal symptoms and reduce drug cravings along with counseling and behavioral therapies for the treatment of substance use disorders.

Though MAT is recommended by The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration for treating OUD in pregnant women, there are barriers that keep it from broad acceptance. Lack of funding, specialty providers and training can stand in the way.

CHS, in partnership with the University of Tennessee, studied the effectiveness of MAT in limiting neonatal abstinence syndrome in newborns and increasing sobriety for women following their pregnancy. We used information from our integrated care clinic with the goal of developing recommendations for the Tennessee Department of Health on how to optimally manage pregnant women with OUD.

Integrating medication-assisted therapy, behavioral health and pregnancy care

The integrated maternal care program at CHS focuses on whole-person care that includes MAT, behavioral health and OB-GYN services. This holistic approach recognizes the overlapping dynamics of mental health and substance use disorders. It leads to more comprehensive screening, timely interventions and the ongoing support needed to address the chronic nature of addiction.

Pregnant women who are identified as potentially having OUD are referred to CHS’s high-risk OB-GYN specialty clinic. During their initial visit, they have a substance use history and assessment taken along with other prenatal tests. Women consult with a case manager who can help them apply for insurance or any other needed social support. A behavioral health assessment is also taken by a clinical psychologist, and individuals meet with a psychiatrist for medication management as necessary.

According to the study, 91.7% of pregnant women who were addicted to opioids had a concurrent psychiatric diagnosis.3 Evidence shows that integrating mental health and addiction treatment improves outcomes because behavioral health can contribute to the development of a substance use disorder or occur alongside it.

From their first appointment, women receive a tailored treatment plan that meets their individual needs, including support for any substance use or mental health diagnoses. Throughout their pregnancy, women undergo intermittent drug testing. When medication is deemed appropriate to assist with opioid addiction, it is provided by a collaborating substance use disorder specialist.

Women return to the clinic the week after giving birth to receive depression, anxiety, or any other mental health condition management. Women can also enter an intensive outpatient program or another substance use disorder treatment program, if needed at that time. Women also receive contraceptive counseling from a specialist working collaboratively with the Knox County Department of Health.

Evaluating the outcomes and looking toward the future

Infants born to women in CHS’s integrated care program were evaluated by neonatologists for evidence of NAS at birth. At the end of a two-year study, CHS saw a positive correlation between the integrated care program and lower NAS rates.

In total, 37 women who used opioids and received care at the CHS integrated care women’s clinic were identified. Of those, 65.2% of babies were born free of NAS. Although not statistically significant, the trend was consistent with Tennessee Surveillance Data on NAS outcomes at the time. That data showed that 68.9% of NAS cases were attributable to substances prescribed to the mother by a health care provider.

In the time since this first study, CHS has continued providing integrated care to pregnant women who are facing OUD. We are also expanding our work with new models that care for patients as a family unit. The time following birth is a critical time for women. By connecting with families at well-child visits, we can often provide care for both the mother and the family.

Improving maternal outcomes and health equity

As we consider ways to support healthy pregnancies, ensure positive birth outcomes and address disparities and health inequities for pregnant and parenting Medicaid members, we must consider the barriers to treatments such as MAT.

Coverage for MAT is still limited, methadone is not covered under every state program, and states have other limits related to how other services are billed, such as case management provided alongside MAT. Not all states reimburse for services such as doulas or other specialists. Many low-income women who can access MAT during pregnancy with Medicaid may lose coverage 60 days post-delivery, while they are still susceptible to relapse.

We must have many ways to help pregnant individuals access the resources and support they need from providers, managed care and their community. Working with our state partners we can develop polices and collaborate to reduce maternal inequities.

To learn more about opportunities to improve maternal health outcomes, read the National FQHC Advisory Board's latest issue brief.

Sources

- CDC Articles and Key Findings About Opioid Use During Pregnancy Opens in a new window

- Incidence and Costs of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Among Infants With Medicaid: 2004–2014 Opens in a new window

- Of 37 women who were identified as using opiates during pregnancy and who received care in the CHS integrated care women’s clinic between March 2012 and October 2014. (Cherokee Health Systems’ Integrated Care Project: Management of Opiate Addicted Pregnant Women to Decrease Incidence of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome)

- Drug Dependent Newborns (Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome) Opens in a new window